On 22 September 2015, one of the most surprising and exciting recent discoveries in Dutch art transpired in the auction house Nye & Company in Bloomfield, NJ: the appearance of one of Rembrandt van Rijn’s earliest paintings, Unconscious Patient.1 After surfacing in the collection of a New Jersey family, it was catalogued as “Continental School, Nineteenth Century” and garnered little attention during the viewing period.2 At the auction, however, it became obvious that two international phone bidders had understood the importance of this painting, and as their bidding intensified way beyond the pre-sale estimate so did the atmosphere in the auction house sales room. By the time the hammer came down in favor of the Parisian dealer Talabardon & Gautier, the puzzled auction-goers were on the edges of their seats. When the auctioneer announced that the newly sold painting was thought to be an early Rembrandt (which the under bidder revealed upon bowing out), the room burst into cheers and applause. Almost immediately, this discovery was featured in newspapers around the globe.3

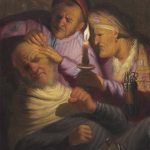

It is not entirely surprising that the connection between the painting and the most celebrated seventeenth-century Dutch artist had not been made earlier, and by more people. The little panel depicting an elderly man and woman attending an unconscious patient, does not feature the strong chiaroscuro effects, subdued palette, and complex psychological tension normally associated with Rembrandt’s works. The painting was also covered in layers of yellow varnish and dirt, concealing many of the subtleties of the composition. Moreover, compounding the difficulty of recognizing Rembrandt’s hand was the fact that his panel had been inserted into a larger panel, and that the composition had been extended on all sides by a later hand (fig 1).

Once the association with Rembrandt had been made, it became clear to all those familiar with Rembrandt’s early oeuvre that Unconscious Patient depicted the Allegory of Smell, part of a series of Five Senses that Rembrandt painted in Leiden around 1625, when he was but a teenager. Three other panels from this series still survive, all of which surfaced in different private collections in the first half of the twentieth century. Just when this series was dispersed is not known, but probably not before the early eighteenth century, at which time, it seems, all of these compositions were expanded after Rembrandt’s original panels had been set into larger ones.4

Among the three other extant works from this series of the Five Senses are two in The Leiden Collection: Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing)5 (fig 2) and Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) (fig 3).6 The other painting, Spectacles Seller (Allegory of Sight), (fig 4), is in Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden.7 Still unaccounted for is Allegory of Taste.

Soon after the acquisition of the Allegory of Smell in September 2015, Rembrandt’s monogram, RHF, was discovered on a drawing of a man wearing a tabard and fur hat attached to the wooden cupboard at the upper right (fig 5), making it the earliest signed painting in the master’s oeuvre.8 When Allegory of Smell was restored and its surface stripped of the yellow varnish that had suppressed the brilliance of Rembrandt’s color, the visual connections to the other known panels from Rembrandt’s series became ever more evident (fig 6). Unlike decisions made when other paintings from this series were restored, in this case it was decided not to remove the early eighteenth-century addition, thus retaining this panel’s composite character (fig 7).

Each of the three panel paintings in Rembrandt’s series of Five Senses in The Leiden Collection feature three tightly-cropped figures who focus on a shared experience in a dark, undefined space. Rembrandt robed his figures in bright pink and light blue attire, which, lit by artificial light sources seen and unseen, provide splashes of color that greatly enliven the images. These surgeons, patients, and singers—young, old, male, female, crude and refined—are unforgettably expressive characters involved in activities that connect the senses of smell, touch and hearing in ways both humorous and empathetic, whether reviving a fainted patient, undertaking a surgical operation, or singing from an open songbook.

Allegory of Smell (fig 6) features a young man wearing a colorful, loosely-draped housecoat, who has fainted and is slumped in a chair. An extremely worried old woman wearing a fur-trimmed hooded mantle tries to revive him by holding a white handkerchief to his nose, presumably one containing smelling salts.9 An equally old man, his right hand covered by a white cloth, holds the youth’s bare right forearm and anxiously awaits to see if the woman’s efforts succeed. His colorful wardrobe, earring and gold chains, as well as the knives, scissors, razors and lotions displayed in a large wooden cupboard, identify him as a barber-surgeon, a profession renowned for its quacks.10 The position of the young man’s exposed forearm indicates that before the youth fainted, the quack was preparing to draw blood from one of the large veins in the patient’s arm, a practice called bloodletting.11 The quack would have used his white cloth to wipe up the blood after completing his procedure.

Patients being bled were generally portrayed with their lower arm exposed, exactly as in the image of another bloodletting (fig 8).12 Once pricked with a lancet (a two-edged surgical knife or blade with a sharp point), the blood would drip into a bowl often held by an assistant. Occasionally patients would faint at the end of a bloodletting, a condition deemed to indicate the treatment’s success. Here, however, one sees neither wound nor blood, neither bandage nor bowl, which means that the young man has not fainted in reaction to such a session, but in anticipation of it. Rembrandt’s image, indeed, not only mocks the elderly woman’s excessive concern about the patient’s condition and the quack’s profession, but also the young man’s lack of inner fortitude.

Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) (fig 3) is an equally humorous depiction of one of the five senses. In a darkened room that hardly suggests a professional atmosphere, a barber-surgeon wields a scalpel to remove a stone from the head of his patient, who clenches his fists and teeth in pain. The only light illuminating the scene is the candle held by an intense elderly woman with a wrinkled face and clenched jaw. Allegory of Touch belongs to a tradition of images hearkening back to the early sixteenth century, in which traveling quacks were shown performing “stone operations” that purportedly cured stupidity by removing the stone of folly.13 One of the most important of these images is an engraving made by Lucas van Leyden (1494–1533) that was widely copied and imitated (fig 9).14 Rembrandt’s figures, with their old-fashioned dress, bulbous hooked noses, gruesome teeth and deeply wrinkled faces, fit firmly within this tradition. Although such surgeries were, in fact, not performed, the phrase “to have a stone removed from one’s head” was part of the popular vernacular and was used to ridicule those considered to be foolish or easily duped.15

Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) (fig 2) similarly depicts an evening scene, but in this instance one illuminated by an unseen light source. In this joyful image, two elderly singers, one male and one female, are joined by a young man who peers down over their shoulders at the large open music book. The bald man, with pronouncedly wrinkled forehead and eyeglasses balanced on the tip of his nose, guides their song with the beat of his raised hand as the old woman, with an equally wrinkled face, leans forward enthusiastically to join him in song.16 The comedy here resides in the advanced age of the two primary singers, for generally images of Allegory of Hearing (fig 10) depict young lovers singing and playing instruments together. Even at their advanced age, however, the couple’s full engagement in the music seems to allude to the ideals of living a balanced and harmonious life. The man’s fur-lined tabard and the woman’s colorful turban are not contemporary attire, and help indicate the allegorical character of the scene.17

Just how Rembrandt devised the various scenes in his series of the Five Senses, and the sequence in which he intended them to be viewed, is not known. Nevertheless, it is clear that with the exception of Allegory of Smell, the young master loosely followed long-established iconographic traditions for his compositional inventions. For example, a number of sixteenth-century artists based their depictions of the Allegory of Touch on Lucas van Leyden’s The Stone Operation.18 As discussed above, Allegory of Hearing often showed young lovers playing musical instruments. There is no precedent, however, for connecting Allegory of Smell to bloodletting. Quite to the contrary, artists like Hendrick Goltzius depicted The Sense of Smell in a series of The Five Senses as young lovers smelling a rose (fig 11). One thus wonders why Rembrandt chose to depict this unusual subject. It is likely that his inspiration was connected to the devastating plague that hit the Netherlands, and in particular Leiden, in 1624, the very year in which he executed The Five Senses. Significantly, the many ailments that bloodletting was thought to cure included the plague.19

The excitement surrounding the appearance of an unknown early Rembrandt at the auction in 2015, and the enthusiastic reactions to this small panel in the art world, contrasts remarkably with the reservations about the other three panels from Rembrandt’s series of Five Senses expressed throughout most of the latter half of the twentieth century. Indeed, the evolution of our understanding of Rembrandt’s work is fascinating, for it has proceeded in fits and starts. One of the most contentious areas in Rembrandt studies concerns the budding master’s early works in Leiden, during the period of his career when he was forging his artistic identity in a boldly aggressive fashion, and when his style evolved with remarkable rapidity. This critical ambivalence is nowhere more evident than in the ongoing critical reactions to Allegory of Hearing and Allegory of Touch after they were discovered and published in the 1930s.

Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) was the first of these paintings to be introduced in the Rembrandt literature. In 1933 Vitale Block published Three Musicians after H. Schneider had discovered it in the collection of the dealer N. Katz in Dieren.20 Block not only attributed the painting to Rembrandt, but he also dated it to about 1626, or shortly before. He noted that the painting had been enlarged on all sides at a later date, recognized that the panel represented Allegory of Hearing, and postulated that it belonged to a lost series of the five senses. By the time of Block’s publication, the painting had already been acquired by the Dutch industrialist and collector Dr. C.J.K. van Aalst who, later that decade, also purchased Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch).

When Van Aalst’s collection was published in 1939, Willem Valentiner, who wrote the introduction to the catalogue, reiterated many of Vitale Bloch’s conclusions, particularly that the two panel paintings, which had been similarly enlarged and were the same size, belonged to a hitherto unknown series of Five Senses.21 Unlike Bloch, however, Valentiner asserted that Rembrandt had also painted the additions. As Bloch and Valentiner recognized, the paintings’ vibrant colors share qualities found in other early works by the young Rembrandt, among them The Baptism of the Eunuch and Balaam and the Ass, both executed in 1626.22 Similarly, the broad, rough brushwork and thick application of paint in the clothing and furrowed brows of the elderly figures are reminiscent of Rembrandt’s Christ Driving the Money-Changers from the Temple, also 1626 (fig 12). Nevertheless, as they rightly perceived, Stone Operation and Three Musicians probably date slightly earlier than Rembrandt’s works of 1626.

The awkward characteristics of Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) and Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) troubled many later scholars, and the attribution of these works to Rembrandt was a matter of much dispute until the early 1980s. For example, in 1956, Knuttel rejected the attribution to Rembrandt, and Rosenberg concluded that the paintings were “odd copies after Rembrandt.”23 Bauch proposed that they were the work of a young Gerrit Dou (1613–75).24 Although in 1968 Wurfbain and Haak renewed the attribution of these paintings to Rembrandt and believed them to be contemporaneous with Christ Driving the Money-Changers from the Temple, Gerson, in his 1969 revision of Bredius, felt that an attribution to Rembrandt was unlikely because of the heavy and dry brushwork.25 In that same year, however, the paintings were exhibited in Montreal and Toronto as by Rembrandt, an attribution with which Held, in his review of the exhibition, agreed. Held proposed a date of execution of around 1622/23.26 In 1976 the two paintings were exhibited in Leiden with an attribution to Rembrandt, this time dated ca. 1624/25.27 In 1982, however, the Rembrandt Research Project relegated the works to the “B” list, meaning that Rembrandt’s authorship could not be positively accepted or rejected.28

In 1987–88 Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) and Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) underwent a radical conservation treatment in which their added panel surrounds were removed.29 By that time, dendrochronological examinations had demonstrated that Rembrandt’s original core images were painted on oak panels datable to the early seventeenth century, but that the added panels were much later in date.30 Moreover, pigment analysis had determined that the overpainting on the extension and original panel of Rembrandt’s Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) contained an eighteenth-century pigment.31 The decision was thus made to remove the painted extensions as well as the extensive overpainting on Rembrandt’s original panels.32 The paintings improved markedly in appearance, and doubts about their attribution to Rembrandt subsided. In volume 4 of Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, published in 2005, Ernst van de Wetering declared that the restoration of the paintings had removed any doubt of their authenticity.33 The paintings have, henceforth, been accepted as an integral part of Rembrandt’s corpus.

In 2006 Bernhard Schnackenburg revisited the hypothesis that the paintings should date to the early 1620s rather than the period after his six-month apprenticeship in 1626 with Pieter Lastman (1583–1633). Schnackenburg noted that the paintings reflect an unrestrained artistic personality, “one in need of practice but willing to take a risk.”34 Van Straten similarly published them as an example of Rembrandt’s pre-Lastman era, executed around 1624/25, solidifying the works’ place as among the earliest works executed by the young master.35

As many authors have noted, these early paintings are rendered with strong chiaroscuro light effects and striking palette of pinks and light blues that relate stylistically to the innovations of Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656).36 Benesch, however, also saw in Rembrandt’s figures the experience of “cruel reality” not evident in the more charming images of the Utrecht Caravaggisti.37 The most likely source for the transmission of Van Honthorst’s manner of painting to Rembrandt is Jan Lievens (1607–74), with whom Rembrandt’s early career is deeply entwined.

At the time that Rembrandt executed The Leiden Collection’s panels, Lievens had been painting independently in Leiden for nearly four years. Jan Orlers, who knew Lievens well, records that the young artist returned from his apprenticeship with Pieter Lastman in 1621. Nevertheless, Lievens probably continued his training in Utrecht, since his paintings from 1622–24 fully reflect the latest artistic achievements of Van Honthorst and the other Utrecht Caravaggisti.38 Rembrandt completed his own three-year apprenticeship with Jacob Isaacsz van Swanenburgh (1571–1638) in 1624, but there is no information about what he subsequently did to advance his artistic career.39 It is entirely possible, even probable, that in 1625 Rembrandt studied with his Leiden compatriot Jan Lievens, perhaps even sharing a studio with his friend before continuing his tutelage under Lastman in 1626.40 Significantly, the model for the youngest member of the group in Rembrandt’s Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) is Lievens himself (fig 13).41

In theme and execution, these paintings are remarkably similar to Lievens’s work from the first half of the 1620s. Much as with Lievens’s Allegory of Five Senses of ca. 1622 (fig 14), they feature tightly cropped, half-length figures in brightly colored dress. The tight pyramidal groupings, flattened backgrounds, and strong chiaroscuro light effects are also similar to those in Lievens’s Tric Trac Players of 1624/25 (fig 15). Rembrandt’s bold brushwork, which endows the compositions with a sense of immediacy, also resembles that in Lievens’s early paintings.

Though Lievens was an important influence on Rembrandt at this stage of his career, Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell), Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) and Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing) also demonstrate Rembrandt’s own inventive personality. Lievens worked on a large scale, which embues his figures with both grandeur and gravitas. Rembrandt’s works, on the other hand, are relatively small, and anticipate the scale of painting that he would gravitate toward in the late 1620s. Writing around 1628–29, Constantijn Huygens reflected on the two artists’ different manners of painting:

So off-hand I would venture to suggest that in precision and liveliness, Rembrandt is the superior of Lievens. Conversely the latter wins through grandeur in conception and in the daring of subjects and forms. Everything this young spirit strives for must be majestic and exalted. Rather than conforming to the true size of what he depicts, he gives his painting a larger stature. Rembrandt, on the other hand, would rather concentrate totally on a small painting and achieves a result on a small scale that one looks for in vain in the largest paintings of others.42

One important and particularly intriguing question is whether, as has been generally assumed, these tightly cropped images reflect Rembrandt’s original intent. Could it be that the eighteenth-century additions actually reflect, and even replicate, Rembrandt’s original painted compositions? This question is certainly pertinent after the discovery of Allegory of Smell, where the eighteenth-century addition to the panel has remained intact. The tight cropping of the main figure is so illogical—the tips of his fingers and the back of his head are both cut by the edge of the panel—that one doubts the cropping represents Rembrandt’s intent. Moreover, the pictorial elements in the addition are so closely integrated with those in Rembrandt’s original design that it seems hard to believe they were a later invention. It is difficult to identify the location of the surgeon-barber’s tools without further knowledge of the chest that holds them, as revealed by the chest on the addition. Finally and most tellingly, the spout of the rounded alembic (glass distillation vessel) painted on the extension behind the surgeon-barber extends onto Rembrandt’s original.

Similar arguments can be made with Allegory of Hearing, the only other instance where the eighteenth-century addition is still preserved, although separated from Rembrandt’s original panel.43 Strikingly, the extended hand of the young singer and the candle lighting the scene are both found on the painted extension (fig 16). Candle-lit scenes in Dutch art from this period virtually always include the actual candle, albeit sometimes with the flame visible and sometimes with it hidden. The extended hand of the third singer over the candle is also quite logical for Rembrandt’s composition.

One of the fascinating phenomena in Leiden paintings over the course of the seventeenth century is that a number of artists did expand their compositions by inserting panels into larger ones. Generally, when these expansions were made, the core panel was set into a customized, shallow opening in the larger panel, so that the reverse of the larger panel showed no evidence that this procedure had occurred. The reasons for this composite panel structure are not known, but it is remarkable how often one finds it in works by such artists as Gerrit Dou and Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635-81).44 Sometimes these extensions seem to have been conceived and executed at the time that the work was created, and sometimes paintings were enlarged at a later date by the original artist. Occasionally, panels were inserted into larger panels by later artists, who then also expanded upon the original compositions of their predecessors.

The question remains as to whether Rembrandt also worked in this manner when painting the series of Five Senses. One solid bit of evidence that supports this hypothesis is related to Rembrandt’s painting of 1626, Christ Driving the Money-Changers from the Temple, which is signed RHF, exactly as is Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell). This work was also expanded by being inset into a larger panel. Although this extension was removed in 1930 and is now lost, an old photograph of the enlarged composition suggests that the extension was painted by Rembrandt, or at least based on his original composition.45

Should Rembrandt have conceived his depictions of the five senses in such a composite manner, then the question remains: what happened to these original extensions that persuaded some eighteenth-century restorer/artist/dealer/owner to remove and replace them? Did the larger panel develop splits or warp? Did the paint not adhere properly to the ground so that it was flaking or otherwise unstable? Unfortunately, there is apparently no way to know what might have occurred that necessitated such a radical reworking of the paintings in this series.

Whatever the historical circumstances surrounding the dramatic structural changes that occurred in the early eighteenth century with Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell), Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch) and Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing), these works offer special insights about Rembrandt’s artistic beginnings. In these paintings one sees how he, as a young man, experimented with the colors and brushwork that would so define his later work, and how he began to manipulate light and shade in a manner that became a trademark of his art. Above all, the three paintings reveal Rembrandt to have been, from the outset, impressionable yet independent, influenced yet innovative. In other words, they show the makings of the master.