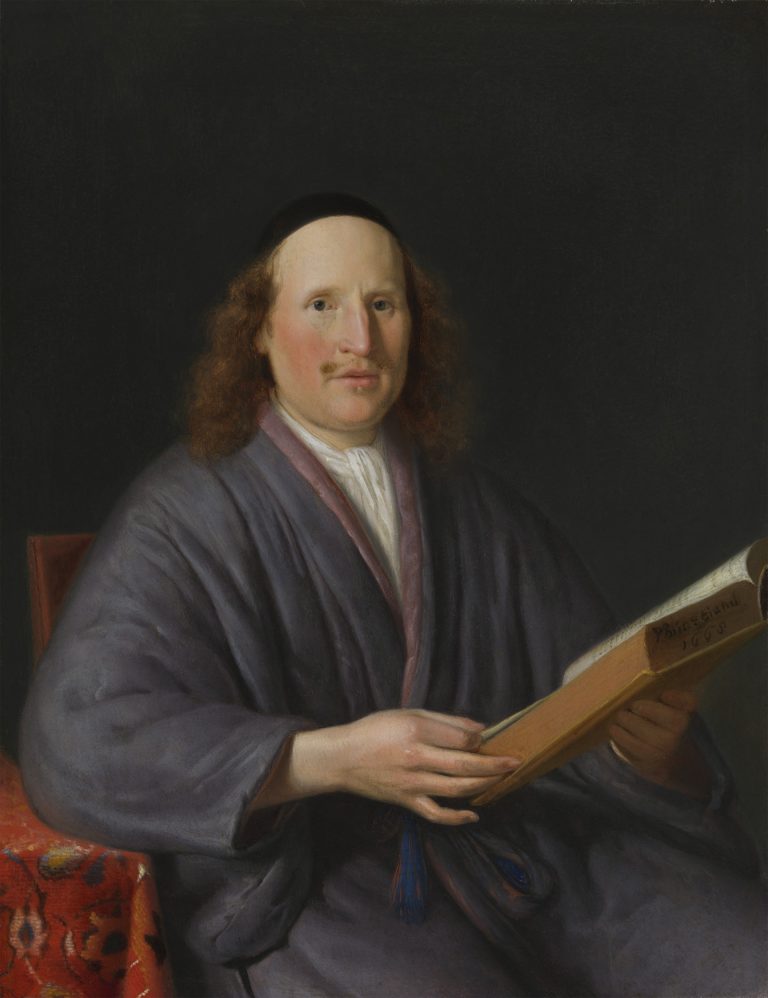

This small portrait on copper depicts a seated man wearing a slate-blue robe who looks alertly at the viewer. He is about to turn the page in the book that he holds in his left hand. The book and the long nails of his elegant right hand establish him as a man of learning and leisure, but Pieter van Slingelandt’s painting is devoid of attributes that might identify him or indicate his vocation. The table supporting his right elbow is covered with a red oriental carpet providing a colorful anchor for the composition.1 Van Slingelandt has used a uniform light to isolate the unknown sitter against a background so dark, one can scarcely discern the edge of the man’s black skull cap. Wispy brown curls further frame the man’s face, in which quizzical eyes compete for attention with the prominent nose.

The man’s robe was known in the Dutch Republic as a Japonse rok (Japanese robe). These loose-fitting and padded robes were modeled on the precious silk kimonos (Keyserrocken, imperial gowns, or schenckagierocken, gift gowns) that the Tokugawa Shogun gave to high-ranking officials of the Dutch East India Company during their annual visits to Edo, Japan. The Japonse rok was worn indoors by men and women alike to ward off the cold.2 This slate-blue robe with its turned-over collar is very similar to the one worn by the standing man in another portrait by Van Slingelandt (fig 1), even if the latter robe seems much silkier and bulkier. It is unclear whether the brown trim of the collar is a strip of fur or the edge of a woolen padding that has been turned over.

One of Gerrit Dou’s (1613–75) most talented students, Pieter van Slingelandt was so adept at emulating his master’s meticulous techniques and compositional elements that his best work has often been attributed to Dou.3 The smooth modeling of the sitter’s face and hands echoes the latter’s finest brushwork, but this figure does not match the energetic physicality of Dou’s portraits. The diminutive size of Van Slingelandt’s half-length, seated portrait would have been rather unusual in the first half of the seventeenth century, when life-size portraits were the norm, but fits fully within the trend toward the smaller likenesses painted after the middle of the century by masters such as Gerard ter Borch (1617–81) and Caspar Netscher (ca. 1639–84).4 Gerrit Dou also produced several small portraits, including the delicate oval Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1655 (National Gallery, London) (fig 2), and Portrait of Dirck van Beresteyn in the Leiden Collection (GD-111). Dou’s student Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635–81) also painted meticulous works in small format, a number of which are in the Leiden Collection, as, for example, Portrait of a Fifty-Two-Year-Old Man (FM-104).5 The keen interest that Leiden patrons had in commissioning their likenesses from masters such as Dou, Van Mieris, and Van Slingelandt is evident in the large number of their portraits in the Leiden Collection. The refined technique of these fijnschilders made them eminently equipped to do their sitters justice on small panel or copper supports.

Small, precious portraits like this one by Van Slingelandt were time-consuming. Portrait of a Man Reading a Book dates from the phase in the artist’s career when he was known to spend prodigious amounts of time finishing his works, resulting, in this instance, in a finely rendered, charming portrait that retains an engaging, lifelike character.6